by Nicky Dempsey

The near-unanimous support for austerity policies in the ruling classes of the main capitalist powers is showing signs of strain. This is not because there is some recognition of the social and economic damage from the crisis, nor because of the valiant level of social resistance in some countries, or even because of the entry of populist and other unpredictable parties of the right.

The first stirrings of capitalist opposition to austerity arises because it has undermined its own vital interests, namely the stabilisation of profits and their eventual restoration.

Criticisms of austerity have emerged from within the governments of Italy, Spain and Belgium. They have achieved semi-official sanction from EU Commission President Manuel Barroso and even from the IMF.

Of course, the substance of the critique is extremely limited and the policy alternatives do not amount to a break with austerity.

The new Italian Prime Minister Letta, for instance, says he will postpone a new property tax, which was a key pledge of Berlusconi in the recent election. But it will be replaced by some unspecified new taxes at a later date. Similarly, the Belgian government says it will embark on a series of tax cuts in an effort to stimulate growth.

This does not alter the essence of austerity, which is to transfer the burden of the crisis from capital to labour. No government minister in Europe is advocating a let-up in wage reduction, cuts to government spending or increased investment led by the state.

But postponing some of the harshest of these measures in some countries and turning towards tax cuts does indicate a genuine concern about the trend in the economy and its effect on profits.

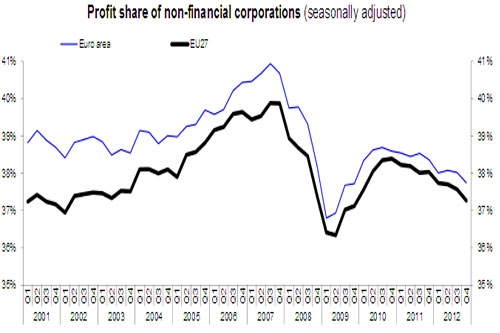

The absolute level of profits has fallen in both the Euro Area and in the EU as a whole (in Britain profits are effectively stagnant). This is the principal reason for the first indications of bourgeois concerns that austerity can be too harsh.

These concerns are amplified by the influence of the wing of the IMF, which represents predominantly the interests of the US. The renewed recession in Europe shrinks one of the US’s principal overseas markets. It is becoming critical of the negative impact on growth because this in turn hurts the profitability of US firms operating in Europe.

The volume of the criticism is increasing just at the time that the US recovery is slowing to a crawl. One of the main factors contributing to the US slowdown its own form of austerity, the ‘sequestration’ of reduced government spending.

The recent cut in interest rates by the European Central Bank is a measure of the renewed concern about economic perspectives.

This was opposed by representatives of German capital, including on the council of the ECB but also by Chancellor Merkel. It is frequently and incorrectly asserted that this German intransigence arises from some sort of monetary or fiscal masochism, or even because of some alleged folk memory of inter-war hyperinflation. In fact, German inflation is currently little more than 1% and heading lower. German industry is an importer of raw materials and a producer of high value-added finished goods. This explains its determined strong currency policy and reluctance to cut interest rates towards those of its main competitors.

But these policies run counter to the interests of many European economies, who are net importers.

There is no suggestion that there will be any softening of the severe austerity policies in the economies where there has been a bail-out. The Greek parliament has just passed legislation allowing the firing of public sector workers, as has the Portuguese government. In Ireland, the government has been threatening across-the-board 7% public sector pay cuts. The most extreme impositions of austerity will continue unabated.

The austerity policy has failed to promote growth, as its ideologues had assumed. It is clear that actions such as cutting interest rates belie the notion that the crisis is caused by government spending. IMF criticism centres on the absence of growth. And tax cuts demonstrate that the deficit is not paramount and that governments can act.

All of these show that the contradictions of the austerity policy are sharpening and that anti-austerity forces can exploit them. As a result, the anti-austerity left will have increasing room to mount its own arguments against austerity and in favour of promoting growth instead.

In Britain the next major opportunity for that is the People’s Assembly Against Austerity. Register here.